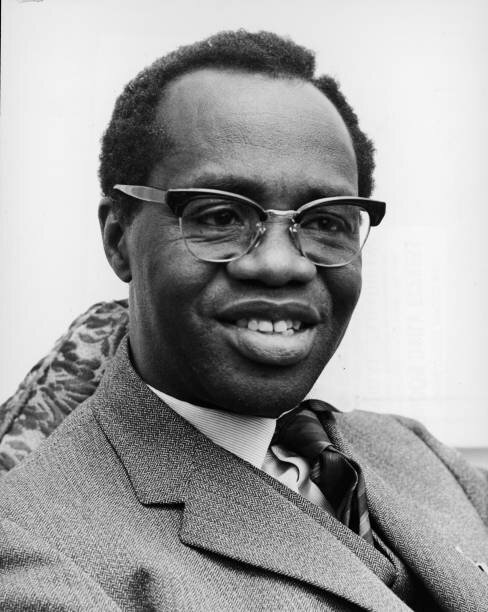

Today in History, exactly 42 years ago, Dr. Kofi Abrefa Busia, Prime Minister of the 2nd Republic of Ghana died from a heart attack in London on August 28, 1978. His Government was overthrown by the army under Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong on 13 January 1972.

Dr. Kofi Abrefa Busia was Prime Minister of the 2nd Republic of Ghana. In 1951 he was elected by the Ashanti Confederacy to the Legislative Council. In 1952, he was Leader of Ghana Congress Party, which later merged with the other opposition parties to form the United Party (UP).

As leader of the opposition against Kwame Nkrumah, he fled the country on the grounds that his life was under threat.

By late 1958 Nkrumah was prepared to detain their leading members, and by the next year he had passed a law unseating any Council member absent for more than 20 sessions. The law was supposedly aimed directly at Kofi Abrefa Busia, whose scholarly commitments took him all over the world. Threatened by immediate detention, Busia left Ghana, in circumstances that have never been adequately explained.

The next seven years were spent in exile, with Leiden and then St. Antony’s College, Oxford, as Busia’s academic base. If Busia had been an unlikely opposition leader in Ghana, he was even more so in exile. But he was now too committed to the struggle against Nkrumah to settle easily into the scholarly life, although he published one book, The Challenge of Africa, and some articles during these years. His testimony to the U.S. Congress against American aid to Ghana caused some resentment. Except perhaps in French circles, it was felt everywhere that if Nkrumah were overthrown it would not be by forces that Busia could hope to command. What was underestimated was the extent to which a revulsion had spread in Ghana against everything Nkrumah symbolized, which would rebound to Busia’s benefit.

Kofi Abrefa Busia returned to Ghana in March 1966 after Nkrumah’s government was overthrown by the military to serve on the National Liberation Council of General Joseph Ankrah, the military head of state and was appointed as the Chairman of the National Advisory Committee of the NLC. In 1967/68, he served as the Chairman of the Centre for Civic Education. He used this opportunity and sold himself as the next Leader. He also was a Member of the Constitutional Review Committee. When the NLC lifted the ban on politics, Busia, together with associates in the defunct UP, formed the Progress Party (PP).

In 1969, the PP won the parliamentary elections with 105 of the 140 seats contested. This paved the way for him to become the next Prime Minister. Busia continued with NLC’s anti-Nkrumaist stance and adopted a liberalised economic system. There was a mass deportation of half a million Nigerian citizens from Ghana, and a 44 percent devaluation of the cedi in 1971, which met with a lot of resistance from the public.

Once in office, Busia wielded strong executive powers. He instituted a stringent austerity program. The chief question that was posed by the election and Busia’s years in power was whether this once reluctant politician was sufficiently in control of his own party, increasingly dominated by little-known but strong-willed younger men, and whether he was sufficiently farsighted to lead Ghana out of its economic troubles and its increasing ethnic and political bitterness. Although his commitment to a parliamentary system was nowhere in question, he authorized some actions and tolerated others that gave rise to the old doubts and some new ones as well. The defeated opposition was further enfeebled by the successful barring of Gbedemah even from membership in the new Assembly, a seat he had overwhelmingly won in his district.

Widespread discontent led to a second military coup on January 13, 1972. The presidency was abolished and the National Assembly dissolved under the regime of Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Kutu Acheampong.

Kofi Abrefa Busia spent his final years as a lecturer in sociology at Oxford University. Of the colonial period, Busia wrote that “physical enslavement is tragic enough; but the mental and spiritual bondage that makes people despise their own culture is much worse, for it makes them lose self-respect and, with it, faith in themselves.” Part of the intellectual liberation in Africa has come through the systematic analysis of African institutions by Africans; Busia’s major study, The Position of the Chief in the Modern Political System of the Ashanti (1951), was a ground breaker in this regard. Moreover, Busia personalized the commitment to freedom of the African intellectual, and his writings on the relevance of democratic institutions to modern Africa found a wide audience. He died in London on August 28, 1978.